Hey, dear reader —

I’ve got a few different things for you today:

A brief summary of takes regarding Nick Quah’s latest for Vulture;

A Q&A with Marty Michael, whose company Headgum produced the hit podcast Dead Eyes;

An article I published in Hot Pod last year titled “The Undervalued Work of the Audio Producer.” I am republishing it this week as a nod to all the people working hard to produce beautiful and innovative works of audio (and because I own it now — huzzah!).

One last thing: if you’re following the story of Adnan Syed’s release from prison, I recommend listening to Brook Gladstone’s interview with lawyer and advocate Rabia Chaudry on this episode of On the Media.

Alright, let’s get to it —

Welp, turns out The Squeeze isn’t the only place for gossip in podcasting!

This past week every gathering of podcasters from here in California all the way to — well, at least Brooklyn — couldn’t stop talking about Quah’s latest for Vulture: “Podcasting Is Just Radio Now.” In it, Quah argued that the industry hasn’t produced a juggernaut short-run/narrative success since the days of Serial, or at best, 2017, when Serial Productions released S-Town.

And — c’mon, of course you picked it apart in your various chat groups and audio nerd Slacks. A piece with that title, that opens with the phrase “podcasting was once powerful,” and describes the industry’s earliest days as “a digital backwater of chatcasts and recycled radio”— it’s begging for a reaction!

The public discourse was spicy, too, even prompting a mysterious someone to create a Nick Quah parody Twitter account (not the first time!).

Quah’s piece inspired it all — praise, rage, sub-tweets, even poetry:

While I can’t wade into the depths of this discussion this week (but happy to chat about it on your podcast or Twitter space), something podcast host and Penn State journalism instructor Jenna Spinelle wrote in an online post resonated with me:

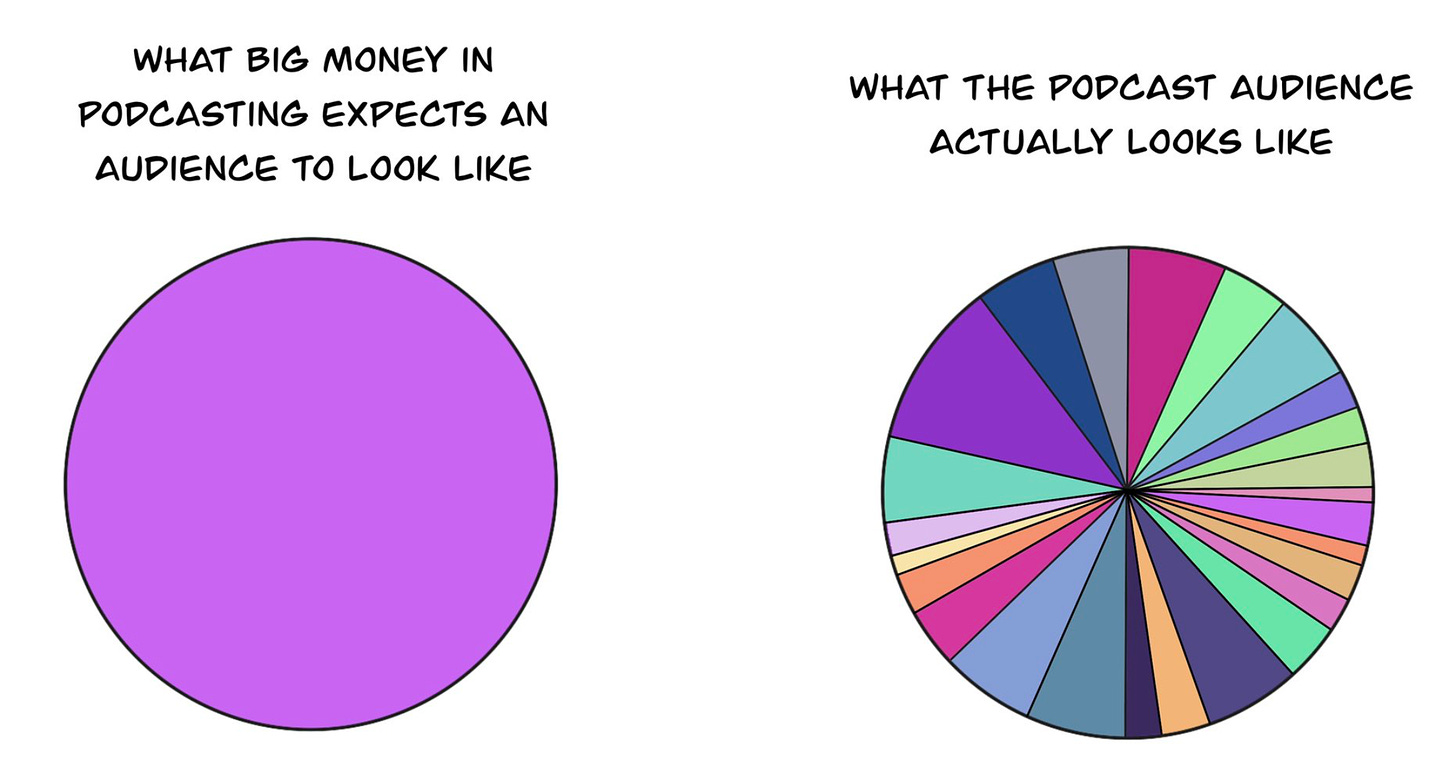

I summed up the article to my students yesterday by saying that the money in podcasting is pushing toward bigger, more general audiences while the audiences themselves are becoming more niche. The industry hasn't yet figured out a way to reconcile the two and I wonder how many of the big players are really interested in trying.

I think she nails it. My sense is that new listeners — at least those in the U.S. — still enter podcasting on the strength of word-of-mouth recommendations but stay for the shows that meet their specific interests.

If that’s true, and audiences are too niched-out to support one-size-fits all blockbusters, will podcasting’s top players continue to pour money into the space over the next five, ten years? And if they don’t, how much will it matter to the rest of us?

Q&A With Headgum Studios Founder Marty Michael

In Headgum’s Dead Eyes actor/comedian Connor Ratliff “embarks upon a quest to solve a very stupid mystery that has haunted him for two decades: why Tom Hanks fired him from a small role in the 2001 HBO mini-series, Band Of Brothers.”

I reached out to Headgum’s co-founder Marty Michael because Dead Eyes was a bona fide hit — not a bananas-level blockbuster, but the kind of show I heard about from both podcast insiders and random members of my extended family. I asked Marty if he would answer a few emailed questions about hit-making and he obliged.

This has been edited for length.

Skye: What’s your take on the Nick Quah piece? Are blockbusters “essential” to the medium’s growth?

Marty: I have thoughts. First, there really isn’t any way to know what is considered a hit in podcasting. That level of measurement — like Youtube plays or box office numbers — simply doesn’t exist. That said, I believe there are far more “Yellowjackets” in the podcasting world than the article suggests and I think that those mid-level successes are what keeps narrative podcasting thriving.

Skye: Do you think it would be possible to recreate the success of Serial at this point?

Marty: Serial arrived just after Apple had baked its podcast app into the iPhone. The conditions were perfect for a cultural phenomenon.

Skye: For the sake of discussion, let’s say creating blockbusters is essential. What gets in the way of creating them?

Marty: Creators trying to recreate the alchemy of what made an existing podcast successful. There is no magical formula to achieve blockbuster success. We are constantly surprised by what succeeds and what doesn’t. We’ve learned not to try to make a hit show, just a very good one.

Skye: Would you describe Dead Eyes as a hit podcast?

Marty: Absolutely. It was a critical darling, received considerable attention and love from A-listers, and from a business perspective, it was profitable. But more importantly, the show resonated with so many people who have haunted by heartbreak and losses and wished for the opportunity to navigate those feelings and get closure.

Skye: What’s the backstory on how Dead Eyes came to Headgum?

Marty: Dead Eyes was made as a pilot for another comedy network which ended up passing on the show. A friend of the network, [actor] Ben Schwartz, reached out to [co-founders] Jake [Hurwitz] and Amir [Blumenfeld] and told them they had to check it out. They loved it; they saw that Connor could use this narrow entry point to explore greater themes around the human condition. We also had the perfect producing and editing team in place at Headgum: [senior engineer] Mike Comite, [producer] Harry Nelson, and [head of content] Clare Slaughter. In a very Dead Eyes way, the show snatched success from the jaws of failure.

Skye: Will there be another season of Dead Eyes?

Marty: We’re currently anticipating what Connor is planning for season 4. We feel like the Dead Eyes question has finally been answered, but the story is just getting started.

The Undervalued Work of the Audio Producer

This piece originally appeared in the Mar 23, 2021 issue of Hot Pod.

Earlier this year, eleven producers, editors, and engineers who had been hired by Condé Nast Entertainment (CNE) to create weekly flagship podcasts for its WIRED, Vogue, and Pitchfork brands posted an open letter detailing the experience of working for, and eventually leaving, the media company. The letter alleged a work environment in which management had little understanding of the resources and time required to produce high-quality podcasts, where staff was consistently left in the dark in regards to long-term planning and job security, and employees were viewed as interchangeable and easily replaceable.

“It was very chaotic,” Ninna Gaensler-Debs, who was hired to work on the Get WIREDpodcast, told me over the phone last week. “There was a lot of confusion over what the roles were going to be. We were very much making it up as we went along. We were just trying to keep up with production, and we were super understaffed.”

Eventually, the group was successful in convincing CNE executives to add support, and the audio team achieved something akin to a production groove. But those gains didn’t last for long. According to the letter, CNE then abruptly outsourced The Pitchfork Review podcast to an external production firm. Its former staffers were told that they could either leave the company or find a place on the Get WIRED team.

Shortly thereafter, the In Vogue podcast team learned their jobs would be terminated as well. “What was shocking was having the experience of really, truly being seen as a cog in a machine,” Megan Lubin, a producer on the In Vogue project, told me last week.

Gaensler-Debs claimed that during a final meeting with management, a CNE vice president — who was theoretically responsible for the Get WIRED podcast — confessed that she hadn’t listened to a single episode of the new show. “That will forever be what sticks in my head,” said Lubin. By January, nearly every person hired by Condé Nast Entertainment to create its slate of flagship podcasts had left.

(When reached for comment, a spokesperson for CNE wrote back: “Our new leadership team at Condé Nast Entertainment cares deeply about our partnerships with talent and the teams who help produce our content… We know that the podcast industry is highly competitive right now and are laser focused on providing the very best experience for the teams that work with us.”)

When I asked Gaensler-Debs how she feels about the experience now, she didn’t hesitate with her response. “It was so frustrating and dehumanizing at a corporate level, but the way that this group of audio producers came together and supported each other was really heartening and powerful and made me feel hopeful for audio.”

It appears evident that a key dynamic in the CNE situation was a basic lack of understanding, on the part of Condé Nast executives, around the role of production staff and the work it takes to create the kind of audio product they were expecting. This, to some extent, is further rooted in a general confusion and vagueness around what producers actually do — which, in talking with over a dozen producers and industry folk from different corners of the podcast world over the past few weeks, seems to be a common affliction.

If you look up the job descriptions of “podcast producers” online, you’ll find that they often vary tremendously, with responsibilities that can include conceptualizing the arc of a show or an episode, conducting research, writing interview questions and scripts, pre-interviewing guests, editing, leading calls with clients, determining show policy, managing budgeting, scheduling, booking, travel, invoicing, etc. These lengthy descriptions imply that the job is typically somewhat fluid and that applicants need to be prepared for whatever comes their way.

However, according to the people I spoke with, such expansive expectations often make it challenging for producers to get hired at the appropriate level, set limits, negotiate raises, claim credit for their contributions, and more.

“The vagueness of the word producer has haunted me — us, our community — forever,” Keisha “TK” Dutes, executive producer of Spoke Media and former producer of shows including Thirst Aid Kit and Rise Up Radio, told me on the phone earlier this month. “It’s vague in a way that serves everyone except for the makers, the producers. When I’m trying to explain my job to outside people, sometimes I just shut down and say, ‘I make the show.’ Like I made it. See the script? I wrote that. See the microphone? I set that up. Hear the music? I told them where to put it and how to fade it.”

Dutes said that, because the role of producer has become a repository for numerous jobs within podcasting, the expectations of a single person’s role can easily get out of sync with reality. “We love this job,” Dutes continued. “We love it through abuse. We love it through racial reckonings. We love it through unfair wages. We love making audio, right? And because of that, a lot of folks have been taken advantage of.”

Dutes is quick to point out that there are places, including Spoke Media, where she is an executive producer, where management has been thoughtful about job specifications and has implemented a chain of command that works well. Similarly, a number of producers I interviewed for this story tend to speak positively about their current work culture. But there remains a sense that these stories are exceptions that prove the rule.

Some argue that these gaps persist because podcasting doesn’t have an industry-wide union, perhaps in the same way that SAG-AFTRA supports the TV, film and now influencer industries. (There have been some relationships forged between SAG and fiction podcast creators, but that’s a different story.)

Were the industry to move in that direction, they argue, a union could create a standard set of job definitions and expectations and provide the ability to advocate for fair pay and other benefits. “I think that people are more and more open [to this idea],” said Dutes. “Not only because they’ve seen that it’s possible through other companies but because folks are becoming less shy about asking to be paid a fair wage.”

Industry-wide use of ambiguous job descriptions is further complicated by the invisibility of producers within the creations themselves. After getting hired, the standard expectation at most podcast shops is for producers to largely exist as behind-the-scenes staff. This, of course, is true for things like film and television production as well, but those are established industries with strong histories of labor, and in the relatively newer and less broadly understood podcast business, the unseen nature of most producers can translate to a lack of progression in the wider education of hiring companies — and a general lack of power in the face of companies who should know better.

Some within the industry have suggested that this dynamic perpetuates a negative cycle, in which advancing as a producer can be inordinately challenging. “We as young producers are often taught implicitly or explicitly that in order to be successful we must make ourselves perfectly useful and mostly invisible,” freelance editor and former New York Times producer Kelly Prime wrote to me in an email last week. “We can be heard and seen behind the scenes and be celebrated for that — to the extent that we are not just willing but also eager to be a ‘team player’ with a ‘positive attitude’ — which is too often code for not pushing too hard for recognition, fair payment and air time.”

It’s worth pointing out that many producers prefer their position as behind-the-scenes contributors and aren’t interested in entering the frame in a more public way. Prime acknowledged this point, saying that it is “more than fine” for producers to stay behind the mic if they wish. Conversely, she pointed out that hosts don’t always want the “power and singularity of voice” afforded by their position either.

“For me, the key here is that every producer should feel like their voice is valued, should they want to use it,” wrote Prime.

Sayre Quevedo, a former associate producer at the New York Times, elaborated on a similar theme when we spoke earlier this month. “What gets lost is that, for the most part, producers don’t do this [work] because they’re interested in pushing out random products for the rest of their lives, but because they have interesting perspectives and experiences and stories they want to tell,” he said.

Quevedo started producing audio at a very early age, and when he was fifteen, he had landed a job as a reporter at Youth Radio in Oakland, which was followed by associate producer gigs at Audible and Latino USA. By the time he applied for a producer role at The New York Times, he had won a Third Coast award and had been nominated for another award from the International Documentary Association. Despite all this, his application for the producer role was rejected. According to Quevedo, he was then offered the relatively junior role of associate producer “as a way to get my foot in the door.”

He took the job, which mostly comprised editing episodes of The Daily for radio — work he said he was overqualified for — hoping he’d advance quickly. However, eight months later, the proverbial needle hadn’t moved. Around this time, VICE approached Quevedo with an offer to be a producer, and he accepted. (He’s currently producing a six-part investigative series over there.)

When I asked Quevedo why he thinks The New York Times and VICE responded to his resume so differently, he was diplomatic. “We’re in an industry that has this influx of money, right? And I suspect that people are just looking for people who can get the job done. There’s not always a lot of thought given to what those individuals bring in terms of their perspective and their backgrounds, or how they could lift or change the show versus perform rote tasks.”

I pressed Quevedo a little harder on the point, and he eventually hazarded a guess. “I suppose the two teams looked at my experience and saw two different things. One group saw the fact that I was doing rigorous journalistic work when I was a teenager as not adding value. The other group saw it as, ‘wow, he’s been doing this since he was a teenager!’”

He added: “I got the inkling that [the Times’ hiring manager] didn’t listen to Latino USA or Youth Radio very often. Which points to a larger issue, the idea being that your labor only has value if it’s something [the manager] recognizes and has listened to.”

Quevedo offered a final thought. “For people to grow and get a chance to actually learn, shows have to be willing to take chances on people who don’t fit their narrow box of what they think their show needs. They need to invest in helping develop them. I do think that’s how we improve the industry as a whole.”

Read this article when it came out and have been stewing over it since! Actually was also super busy launching my own Substack....which is all about narrative podcasts.

My thesis is that part of the problem is that narrative podcasts are just not talked about as a thing. And if we want them to be that, meaning become their own genre worthy of discussion praise and cultural discussion, we actually need to contribute to the discussion.

It’s not enough to have money thrown at it (although necessary). X number of celebs jumping in won’t produce magic alone ... what will make hits is:

- Volume of work (so hits emerge amid organically)

- Audience growth

- actual budgets to make decent shows

- discussion and talk about podcast series from general public

- critics and journalists discussing shows and story and art

- brave disrupters if industry

- talented storytellers making good work

But if they aren’t there, none of this happens.

And if rhymes aren’t even discussed as a genre, with a coherent name and nomenclature, how do we know what we are all supposed to be talking about?

Here’s my contribution:

Www.Bingeworthy.Substack.Com