After KQED Eliminates 34 Positions, Union Boss Says Station Leadership Has "Lost Their Way"

Meanwhile, I Freak Out

Hi everyone — Sorry I didn’t get this out yesterday! Life is bananas!

Today’s agenda:

More details regarding the layoffs at NPR affiliate KQED. If you missed my first two stories about this last week, you can find them here and here;

Why I’m freaking out about this (aside from the obvious reasons);

No she didn’t! Yes she did! A union leader speaks out.

Let’s hit it!

More Details on KQED’s Layoffs

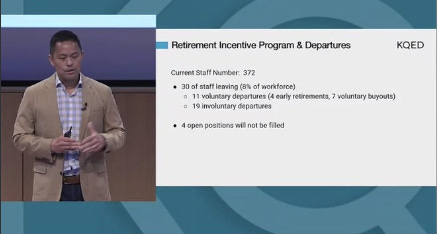

Yesterday at an all-staff meeting KQED CEO Michael Isip shared the following:

30 staff members (8% of the station’s 372 full and part-time employees) are leaving the station:

11 staffers are leaving voluntarily (4 early retirements, 7 voluntary buyouts);

19 people are being laid off.

Four open positions will not be filled.

The cuts have been spread across almost all departments including radio broadcasting operations, membership, corporate sponsorship development, human resources, digital video and podcasts.

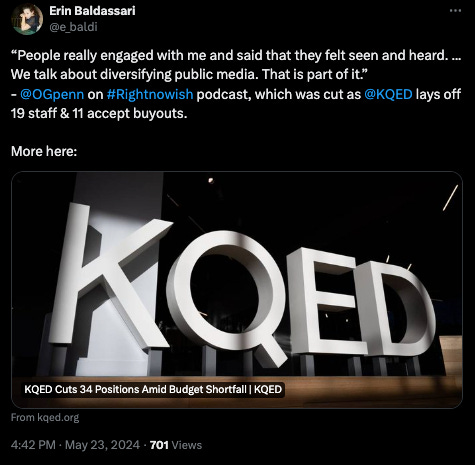

The station is also ending Rightnowish, an award-winning podcast featuring mostly BIPOC voices; its final episode will drop on July 18th. The station announced one layoff as a result of this decision, while a second employee from the podcast team accepted a buyout.

All departing employees will receive:

Two weeks for each year of service (minimum of eight weeks, max of 24);

Payout of unused PTO, as of last day of employment;

Three months of health benefits;

Unemployment benefits;

Outplacement services.

According to a piece reported by KQED yesterday, the station is running an $8 million deficit for fiscal year 2024. Isip said he anticipates that by making these cuts (along with other budget-cutting measures), the station will save $4.5 million annually and have a balanced budget by fiscal 2027.

The CEO also revealed that “in an effort to drive digital growth,” the station has recently launched the KQED Studios Fund, “a $10 million initiative to grow podcasts and online video production that will focus on ‘stories and programs rooted in the Bay Area.’” (Will the fund actually “grow podcasts”? Very sci-fi of them!) Obviously, I’m bullish on (growing) podcasts but when public media people start talking about making videos for the Internet as part of a growth strategy, I get jittery.

Which is actually the perfect segue into —

Why I’m Freaking Out About This (Aside From the Obvious Reasons)

Sometime last week, a current employee (who requested anonymity) sent me a distressing email. “KQED has been making … ‘strategic investments’ to grow new audiences,” the staffer wrote. “Some of these involve building a new app, developing podcasts, and setting ambitious goals to dramatically grow unique visitors to the website.” (The source added that in an effort to support the latter, the newsroom had recently installed an “express desk” to get breaking news up on the KQED website as fast as possible.)

“All this is well and good but it just hasn’t led to audience or revenue growth,” the employee explained. “It’s not clear to me that KQED knows how to monetize these things as well as they know how to monetize radio.”

Spoiler: they don’t. For one thing, in 2024, no one knows how to monetize digital news. Most of the folks who did know at one time or another, have already failed or are in the process of slowly dying (and thanks to Google, the situation just got worse).

But also, monetizing digital is about scale and speed (thus the need for an “express desk” I guess, ugh — it’s a race to the bottom, people!), while funding public radio is about serving a local audience who is deeply engaged. These are two different business models for two different kinds of audience, and they require almost diametrically opposed strategies and expertise. It’s hard enough to get one of those right, much less both! To be clear, it’s a no-brainer that public radio should leverage technology as a way to deepen relationships with listeners and attract new ones, but please, for the love of God, not at the expense of what stations do best (and audiences are willing to pay for): in-depth, news and investigative audio journalism.

The other day, I asked a seasoned public radio person for their take on why public radio seemed to be in such a frenzy to buy, merge with, build out their own digital platforms. This person, who led their station’s successful digital implementation, explained that

Executives become enchanted with the aggregate numbers in digital. They see those big numbers and think, we’ll just monetize our digital side. But it doesn’t work that way. I haven’t seen anyone in public media who has been able to show that you can turn your digital audience into paying members of your public radio station. Digital media is a mass audience product. If you turn a public radio station into a mass product, the relationship with your audience changes; it becomes more transactional. Sure, some people might donate after a station sends out a digital email blast, but those people are likely hooked into your brand because of the work you’re doing on the radio and in on-demand audio. And believe me, those stations are not going to make up the difference by selling ads on their website.

Executives seem to forget that our advantage as a public radio station is hyper-serving a core group of listeners. When you hyperserve your audience, they become loyal members of your brand; they become paying members. Traditional radio fundraising will bring in funds and gifts that are larger and more consistent than anything you'll get from users who click through on an online article or newsletter. And the one thing those donors all love supporting is shoe leather, deep dive, investigative, longform journalism. This message especially resonates right now, when people know that journalism is a shitshow.

And so, when a station has to make cuts because “the digital audience growth we projected to achieve, to help offset anticipated broadcast audiences, has been slower than needed to develop,” — as it says, right there in KQED’s FAQ about the budget reductions — we shouldn’t be surprised.

In fact, we should expect it.

And try not freak out.

But I am freaking out!

And I will not be stopped!

Speaking of which —

A Union Leader Speaks

Yesterday, I obtained a bulletin sent by NABET Local 51 President Carrie Biggs-Adams, to the union’s KQED members (at least nine of the employees impacted by this week’s layoffs are represented by NABET). The letter is long, so in the interest of space, I’m including just a few snippets. But you’ll get the idea.

I grew up watching KQED, loved it, loved listening to KQED-FM as I drove; but I have long been appalled at how they are treating the public trust that is Public Broadcasting. It will be no surprise to people with whom I discuss the future of media in general and KQED, that I believe your employer has lost their way in producing content for broadcast, serving the public in the Bay Area, and curating the community that should be supporting KQED with the money needed to flourish.

… KQED has bought into the idea that streaming, podcasts, and digital are the future – this while the major broadcast networks and companies have been losing money hand over fist trying to get people to subscribe to more and more apps that don’t pay for themselves.

… We must push KQED to understand the value to television and radio – urging them to stop focusing the shiny objects that are digital, podcasts, TikTok, etc. – and do the work to make compelling broadcast products that bring in listeners, viewers, and donors.

I have to say, it’s thrilling to witness someone besides me freaking speaking out about public radio’s distressing fixation on sparkly digital objects (though, with all due respect, public radio should not give up on podcasts, Carrie!).

I just hope the right people are listening.

That’s it for me today!

Have a great weekend and take care of each other out there.

Skye

Postscript

Streaming and podcasting were seen by public broadcasters -especially on the radio side- as a way to increase revenue and grow the audience. In a few cases it’s worked. But for most stations it’s been a fantasy that’s turned into a money pit.